Research

Most landholder members are involved in some aspect of research, such as recording species, particularly those that are in danger of extinction. This can be a direct contribution or via groups of people hosted by a landholder. Contributions made to British Trust for Ornithology, RSPB, surveys on bats, butterflies, moths and grasshoppers are just a few of the many.

Apps for Identification

Useful Natural History Apps: Briefing Note Produced for KLAW Members by KLAW members.

Although many fantastic ID guides exist on the wildlife of the UK, you don’t always have your copy of ‘The dragonflies of Sussex and Kent’ on you when you most need it! Maybe because of this, apps are becoming a popular way of not only identifying species but also recording them. However, it’s not always easy to know which apps to use, and importantly where any records might go. Some KLAW members have been looking into this and provided useful briefings on their experience of using different apps. Many thanks for Sally Edge for providing the first two useful summaries.

Please email the KLAW Chair using this email address: chair@KLAWonline.co.uk if you are able to contribute to this briefing on Apps. For example, if you have used an identification app yourself and have views on the pros and cons.

The KLAW committee have also consulted Tony Witts of the Kent and Medway Biological Records Centre, and had the following useful feedback.

A note from Tony Witts of Kent and Medway Biological Records Centre:

“I would strongly recommend using UK based apps since we have highly developed networks for sharing data that academic institutions don't have as data is often held closely for their own research and funding opportunities.”

Useful Links:

For the ‘Langdon Garden’ project on the iNaturalist website Blog comparing iNaturalist and iRecord click here.

Where To Send Your Wildlife Records? - James Common's site, click here.

App Reviews

iNaturalist

iNaturalist is an online social network of people sharing biodiversity information to help each other learn about nature.” Originally founded in the US, it is now a global non-profit, with localised partnerships – in the UK this includes the Biological Records Centre and the National Biodiversity Network Trust. This means that data generated in the app is fed into our local Kent and Medway Biological Records Centre. Tony Witt of KMBRC has confirmed that iNaturalist is one of three apps (along with iRecord and BTO Birdtrack) that have good data flows and solid verification and validation procedures that assure data users such as KMBRC of the quality of the data.

KLAW and Apps – By Amanda Brookman

I have to agree with James Common, I find iRecord very useful. When I first started attending various wildlife events there was a lot of encouragement for people to record what they saw and iRecord was always the platform recommended. The phone app is very handy for in the field records and the PC based version great for when you’re back at home and have records to submit after you’ve identified what you’ve seen. Its also great for checking your submitted records.

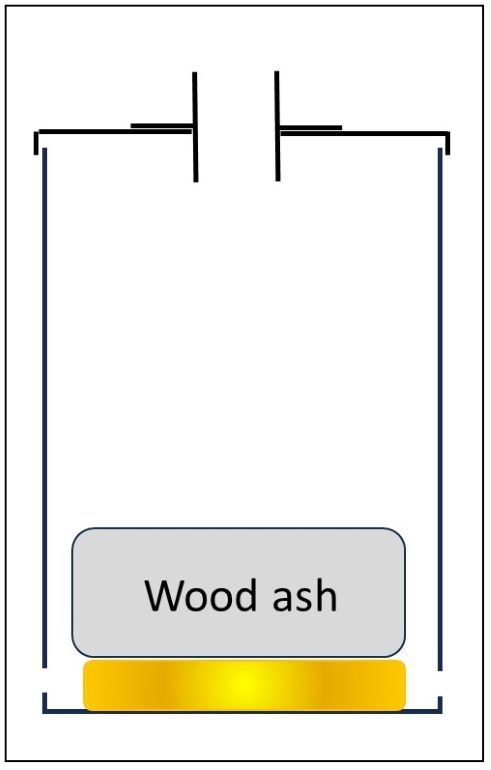

There are also certain groups which have templates for recording that capture info that iRecord doesn’t automatically, such as if you are moth trapping, you select that species list and you will be asked for the kind of trap you have used and enter your data as a list.

There is also specific iRecord app for butterflies, unsurprisingly called iRecord Butterflies, which you can also tweak to include day flying moths. This is a great resource because it includes an ID guide and can be used to record one off sightings or multiple species in a survey area.

There’s also iRecord Grasshoppers, another fabulous app which includes ID help including the sounds of grasshoppers/ crickets and allows you to record them and upload them with your submission to aid verification.

The Kent Moth Group are exceptionally speedy at verifying records and I have found that hoverfly, ladybird, dragonfly and shieldbug records are also usually verified quite quickly too.

Some groups I have found get better verification if submitted through a recognised scheme e.g. BeeWalks, UKBMS or the Garden Butterfly Survey. There is some frustration within the general public that some records don’t seem to get verified, but this doesn’t stop me submitting what I can, you never know when a record may be needed and if we don’t know about something we can’t protect it.

My experience of using iNaturalist – By Sally Edge

From a personal point of view, I have been using the iNaturalist app on my phone for some months and have found it to be very user friendly. I mostly use it to record species that I have been able to photograph (so mostly invertebrates, plants and fungi, rather than birds, mammals or amphibians). I can then view these records in various formats – grid, list, and map. I can also use the map to see other user’s records in my area. Identifications can be verified by other users, and can turn observations from ‘casual grade’ to ‘research grade’. Most of my observations have been verified as research grade. The casual grade ones have not been verified by other users yet, or my image isn’t good enough for a definite ID. You can also use the app as an identification tool (it will look at your image and make suggestions), but I tend to cross-reference with the iPhone ID tool and internet research before making my record. Records can also include sound recordings so could be used for bird song, for example. I have recently used the ‘Project’ function for my garden called ‘Langdon Garden’. This means that anything recorded in the garden, by any user, is listed under the Langdon project. I will encourage visitors to our events to use it, and it may be useful in future if we run BioBlitz type activities.

iNaturalist and KLAW

If other KLAW members created similar projects for their areas of land, we would be able to follow and discuss each other’s observations. Potentially, this could be a great way to build the KLAW community, share information about wildlife on our land, and find common interests/potential projects.

Merlin

Merlin is a bird ID app – described by its makers as ‘a birding coach for bird watchers of every level’. It is created by Cornell University in the United States, and draws on data fed into the recording app eBird, including photos, recordings, and data about when and where observations were made. This user-generated data enables the Merlin AI to identify a bird in real time, quickly and easily. When installing the app you can choose your country location ensuring that the correct data set for your region is installed. It is primarily an ‘identification app’, rather than a ‘recording app’ so not one for sharing bird sightings with UK-based recording centres.

My experience of using Merlin – By Sally Edge

I have found Merlin to be a very enjoyable and rewarding app to use. As a beginner birder it has been great fun being able to use the app to identify the birds singing around me in real time. The app will highlight the names as each bird sings, so if a bird is repeating a call, you have a chance to listen multiple times and begin to recognise the sound by yourself. My impression is that the majority of identifications are correct – only once or twice have I been aware of a mix up (e.g. between a moorhen and a coot). The app also identifies from photos – even blurry ones – with accuracy, and makes suggestions from a description if you don’t have a photo or sound. Highly recommended for both beginner and more experienced bird watchers.

eBird

ebird shares records with the Kent Ornithological Soc. but the licence prevents them from sharing the records further, this is an issue that the wider local records community has looked into but not come up with a solution.

The ‘What’s Flying Tonight?’

One member has found this to be a great way to identify moth species that might be visiting your garden. You enter your postcode and the app pulls data from local moth records, displaying nearby species.

Bird Ringing

One area of research is the bird ringing at several KLAW Member sites. For example, a team of experts has been ringing birds for several years at Mystole Orchard, which is a BTO Constant Effort Site (CES). This study is monitoring how bird populations are changing by ringing at fixed intervals and at the same locations. The data collected from both Mystole and other sites is sent to the BTO. These ringing records cover a range of species, with the sex, age and weight of each bird ringed. The details of where birds were previously ringed are recorded if recaught.

Details of the training essential for safe bird ringing is available by clicking here to go to the BTO web site. This also provides guidance on ringing, the reasons for it and how to get involved.

There are several ringing trainers and groups in Kent, also two Bird Observatories, Sandwich Bay and Dungeness, where people can go to see ringing being done and perhaps to get involved and train if they wish. Always remember that whilst ringing birds is a privilege and very enjoyable, it is a licensed activity and requires quite a commitment to train.